The Google Map shows known Armenian communities in the Central Asian Republic of Turkmenistan. This corrupt and repressive state was ruled by the vainglorious dictator Saparmurat Niyazov from the break-up of the Soviet Union until his death in 2005 and since then by another narcissistic autocrat, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow.

There are perhaps 30 to 40,000 Armenians in the country, living mostly in the major cities indicated on the map. Armenians arrived in Turkmenistan during Imperial Russian times, others during the Soviet era. More recently, more arrived following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Minorities have limited rights in Turkmenistan and, as might be expected, many Armenians with the means to do so have emigrated to Armenia, Russia or USA in recent years .

There is no registered Armenian place of worship in Turkmenistan. The state recognises only Islam and the Russian Orthodox Church (the churches of which are used by some Armenians).

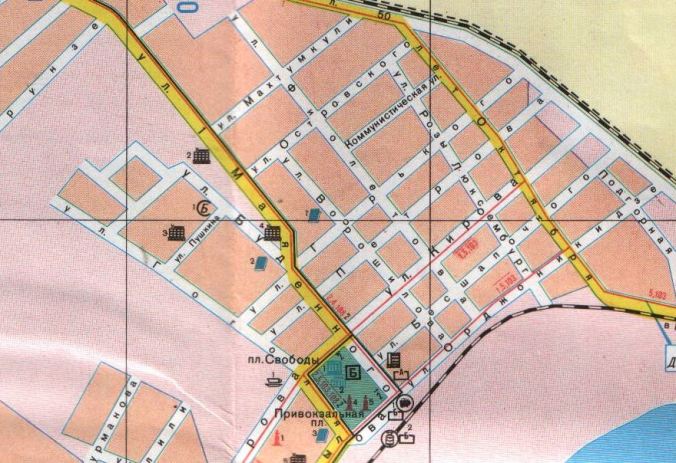

Of the five pre-Soviet-era Armenian churches (one per city shown on the map, except Balkanabat), the last standing was the one in Türkmenbaşy (Turkmenbashi – Russian Krasnovodsk), which was demolished in 2005. The former Armenian Apostolic church here was founded in 1904 but seized by the militantly atheist Soviet authorities in the 1920s and used as a warehouse. According to accounts on the internet, the church stood, decommissioned, at the junction of Pushkin and Lermontov streets. Street names in Türkmenbaşy have, for the most part, been renamed, although the street name Puşkin Köçesi survives in the old town (which was primarily Russian). However, Soviet-era Russian language maps do not show Ulitsa Pushkina and Ulitsa Lermontova as intersecting. Ulitsa Pushkina street was a short road joining Ulitsa Gogolya and Ulitsa Budennogo, both of which ran down to the square Ploshchad Privokzalnaya and the railway station by the waterfront. Ulitsa Lermontova, on the other hand, was further north, beyond the Russian cemetery (in which Armenians were presumably buried, it being the only Christian burial ground in the city) and running off 1 Maya (now Azadi Köçesi). Perhaps, therefore, Gogol rather than Lermontov was meant. Accordingly, the pin on the Google Map has been placed where the former Ulitsa Gogolya (now called Adalat Köçesi) joins Ulitsa Pushkina. In any event, the church survived until 2005, when it was demolished by the Turkmen authorities, despite repeated requests for it to be returned to the Armenian community.

The Krasnovodsk street plan below shows the old Russian town, with Russian street names, during Soviet times. Ulitsa Pushkina can be seen (as “ул. Пушкина”) towards the left-hand side of the map.

You must be logged in to post a comment.